In 1867, Te Ua's nephew Te Whiti, and nephew-in-law Tohu had founded a community at Parihaka, near Mt Taranaki, as a place of peace. 1867 was a year without war and even the warrior Titokowaru remarked, 'This is the year of the daughters, this is the year of the lamb'.

Te Whiti's vision was of an open settlement, a radical departure from the traditional foritified pa.

Parihaka represents today one of the most shameful episodes of New Zealand history.

His people wore white feathers - the raukura or albatross’ white feather of peace - in their hair as a sign of this desire to live in harmony.

Te Whiti was greatly influenced by the Scriptures. He saw his people as a Lost Tribe - but he had the genius of synthesis to incorporate the best of his Maori heritage with the new European ideals.

Unfortunately Parihaka was in the middle of a million acres of confiscated land - even if the land had been confiscated illegaly. That confiscation, in 1863, had been based on a rebellion by the tribe that had simply not occurred.

In 1878, surveyors moved in, and Te Whiti and Tohu initiated protest - the surveyors were removed.

(The Government later made the act of refusing surveyors on land Maori might own an offence punishable by 2 years prison - the West Coast Settlement Act.)

Maori erected fences to keep the pakehas off their property -- and the constabulary pulled the fences down.

To demonstrate that the land was theirs, members of the community would then plough the land by day, and be arrested - but other Maori were arriving to support the movement. As men were tossed into prisons, as far afield as Wellington, more Maori simply arrived to take their places.

Some were famous and noble warriors, and

Te Whiti, as a skilled orator, took the time to remind Pakeha who they were

in his eyes:

"The head of the land - the Queen - is honoured in proportion to

the pomps and vanities of her attendants. Her governors all hold out their

hands for their wages, without which their patriotism would shrivel up."

Naturally European settlers were concerned, and militias formed. Tension, and fear grew.

A Taranaki newspaper even exhorted genocide:

"Perhaps the present difficulty

will be one of the greatest blessings ever New Zealand experienced .. for

without doubt it will be a war of extermination .. this means the death-blow

to the Maori race"

('History of NZ', Rusden)

Below, Te Whiti, the Prophet of Parihaka.

The prisoners were shipped to the South Island.

These protestors were being held illegally.

Colonel Whitmore, now a Minister of the

Crown, knew that, it was,

"impossible to bring these men within the four corners and technicalities

of the law"

and also that if they were tried, they might be

"liberated by the Supreme Court".

Captain Russell, who was to become Minister

of Justice commented that,

"In any case .. these natives .. are really not British subjects

at all."

Thus, Maori had been exhorted to sign a Treaty that would make them subjects of Her Britannic Majesty, with all rights and protections, at Waitangi - but they were to have no rights and no protection when the Government saw such prime land at stake.

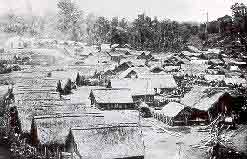

In 1881 the Government moved, and Parihaka was occupied, and demolished, by a 2,000-strong milita under the command of Native Minister John Bryce.

Over a thousand people living there were

ordered to leave, and the leaders were arrested, and held for trial - they

were never tried, as the Government had passed a law the previous year allowing

them to hold the leaders indefinitely, that is, without trial - the Maori

Prisoners Act.

Over a couple of months, in a war of attrition and excess, the prosperous village of Parihaka was systematically razed, homes were looted and burnt, crops destroyed and livestock slaughtered.

The people were forcibly driven out and left homeless, facing a bleak future of extreme hardship, and the settlement was virtually wiped out of existence; maps were redrawn and history was redefined in the attempt to obliterate the memory of Parihaka from the face of the earth.

Two years later, Te Whiti and Tohu were released, and they immediately returned to Parihaka to rebuild, but were again arrested - their utopian dream of a new social order for Maori and Pakeha based on respect, equity, peace and harmony was not realised in their lifetimes.

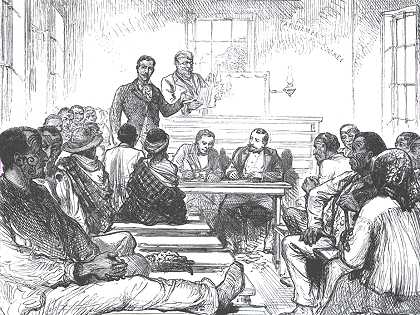

Earlier, in 1880, a 'Maori Parliament' had been convened at Orakei to discuss, among other things, the appointment by the Government of William Fox and Francis Bell as members of a Royal Commission to investigate the confiscated lands in Taranaki.

Bell and Fox, said the Maori, had been largely responsible for the confiscations!

Image below, at Orakei, with Chief Hirini Taiwhanga speaking and Chief Tauhere chairing the gathering..

The lesson to Maori was clear - Europeans would take land - and that the Maori would be considered a second race, a small nation within a larger, European nation.

New Zealand was now established as a jewel in the British Crown. The Duke of Edinburgh had visited back in 1869.

An engraving of the time (Hargreaves & Hearn) features a flower garland, promising "Peace and Plenty"

The "breaking in" of the land was well underway, and New Zealanders believed that if the country was a jewel in the Imperial crown, then it was indeed a bright jewel, perhaps more genteel than it's rude neighbour Australia - and more hospitable than India or South Africa..

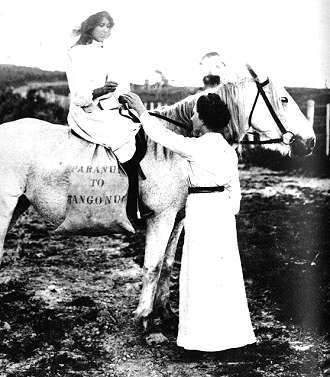

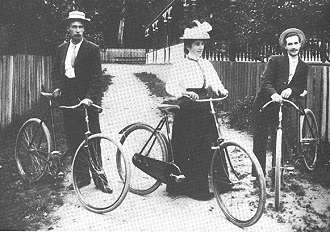

Communication - roads, shipping, and post was well established. Images below, teenage girl on a mail run Paranui to Mangonui, Northland - and keen cyclists.

It was in the 1880's that the NZ economy stumbled however, and many Pakeha simply fled, either to Australia or North America.

Below, dancehall and brothel.

New Zealand's vaunted goldfields had run out, and the kauri forests had been decimated, so there was little else at that time to create a stable economy - despite a phenomenal export in 1883 of nearly 5,000,000 bushels of wheat, and with wool exports becoming a strong feature - by 1886 New Zealand was in the grip of a financial depression.

In 1879 the City of Glasgow Bank had collapsed, and since then credit had been harder to obtain from other banks. The land rush had been built on credit, and now properties plummeted in value and bankruptcies doubled. Prices for wool, and wheat, the primary exports, were falling and unemployment was climbing.

1887 and 1888 were the worst. Some relief schemes for urban unemployed were enacted, but a "special settlement" was also brought into being, where people were given small grants of land in the bush and told to go live there - a subsistence life.

In the cities, men's jobs were filled be cheaper women and boys. Between starvation and a boy's wages, there was no choice.

By the end of the 80's, over a hundred thousand had emigrated.

The Depression faded as adequate refrigerated vessels called at New Zealand and shipped exports to England, where dairy and meat prices remained high.

(image, Wellington Post Office 1886)

New Zealand.org.nz Homepage here