The Maori Wars were perhaps inevitable.

The

opinion that the European was a "civilized" being, ordained by nature

to rule the Maori - an absolute and unquestioned assumption in those times of

colonial acquisition throughout the world - are exemplified in this comment by

Judge Maning, in 1869:

"We

shall live in a dreamland until we fairly conquer the rebel natives and when we

are absolute masters of this country it will be time enough to talk of technical

and civilised justice"

Maori had been having serious doubts about land that had been sold, or that they were being corced into selling - and were attempting to reclaim the land.

In 1841, at Wairau, in the rich Marlborough Sounds, the local iwi refused to allow surveyors access.

Te Rauparaha (below) was there from his Kapiti stronghold, and Te Rangihaeata, who was Te Rauparaha's nephew, to support the local chief.

There was an instant showdown between Maori and armed settlers including the Nelson magistrate, Thompson, and Capt Arthur Wakefield - 15 Europeans were killed almost instantly, as well as 4 or 5 Maori - Te Rangihaeata's wife, Te Rongi, was killed by a musket ball through the head.

Her husband exacted utu by killing the prisoners that were then taken with his greenstone patu, or ax.

FitzRoy, the NZ Governor, arrived personally to mop up, and came to believe that the Maori had been provoked - he decided to leave things be.

Hone Heke, son of Hongi Hika (who started the inter-tribal bloodhsed of the Musket Wars) had become totally disillusioned with the British.

Although he had been the first Maori chief to sign the Treaty of Waitangi, in 1844 he chopped down the flag pole flying the Union Jack at Kororareka. He began flying an American flag on his canoe.

Heke thought about what he had done - and sent a letter to Grey suggesting that the Maori be left to sort out what were their own problems and their own feuds - he was disgruntled not only with Pakeha but also with the Northern Maori, and he felt he had made his point .

"Friend Governor. - This is my speech to you. My disobedience and rudeness is no new thing, I inherit it from my parents, from my ancestors, do not imagine that it is a new feature in my character, but I am thinking of leaving off my rude conduct towards the Europeans.

Now I say that I will prepare another pole, inland at Waimate, and I will erect it at its proper place at Kororarika, in order to put an end to our present quarrel.

Let your soldiers remain beyond the sea, and at Auckland, do not send them here. The pole that was cut down, belonged to me, I made it for the native flag, and it was never paid for by the Europeans. From your fried,

(signed) HONE HEKE POKAI."

He then chopped the flag pole down again, and then for a 3rd time in 1845, forcing the British to erect a pole sheathed in iron, and establish an armed guard - and thus slowly the 'First Maori War' was germinated. It is also known as 'the Northern War' and 'Hone Heke's War'.

Hone Heke attacked the military base and village, and withdrew, leaving fifteen dead soldiers and sailors behind.

FitzRoy was shocked, "Neither I nor anyone else thought of his succeeding in an attack on our forces" he wrote.

The British responded, sending troops across from Sydney, and with about 400 men Lt/Col Hulme attacked one of Hone Heke's pa, near Lake Omapere.

Hone Heke had around 300 men with him, and his ally, Kawiti another 150. The Ngapuhi chief, Tamati Waka Nene, with his 400 men, had sided with the British, so Hone Heke was outnumbered 2 to 1..

The British troops rushed at the pa with bayonets and were repulsed. The Maori were impressed at the British courage - and also by the liberal British profanities.

Fighting continued between Hone Heke and Waka Nene as at Pukenui in mid 1845, where Heke was shot in the leg at the end of the battle, as he attempted to retrieve the body of his ally, Te Kahakaha.

More troops arrived in New Zealand for FitzRoy - outnumbering Hone Heke 6 to 1, the British attacked Heke's pa at Ohaiawai, also known as Waka's Hill, under the command of Colonel H. Despard.

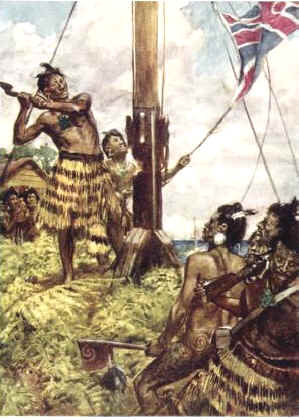

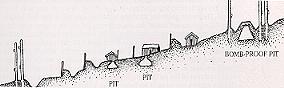

He decided to storm the pa with bayonet - a steep uphill, open charge (image above) - and Waka Nene, a Govt Maori, called out that Despard was a 'stupid man' - ignoring him, Despard sent 100 men to their instant death by musket fire, echoing perhaps in microcosm the same irrationality that saw millions of soldiers mown down in the mud and trenches of World War I..during the battle, Hone Heke did not attack supply wagons, "Where would be the use of our taking the food and powder of the soldiers? How could they fight with us if we did that?"

It cost FitzRoy his Governship - Captain (and later Sir) George Grey arrived to replace him, and it was reported that the Duke of Wellington wanted to court-martial Despard.

The 'New Zealander' published 7 June 1845 in the Bay of Islands, reported that,

"On

Sunday evening last, the barque British Soverign, arrived from Sydney, with the

head-quarters of the 99th Regiment, and following officrs: - Lieutenant-Colonel

Despard, Major Macpherson, Lieut. and Adjutant Dearing, Lieutenants Beattie, Johnson,

Dr. Galbraith, Ensigns Symonds and Blackburn, Dr. Meen, and 200 rank and file.

The brig Victoria, and the schooner Velocity, having on board troops,

sailed, on Tuesday evening, for the Bay of Islands ; and it is anticipated, that

nearly the whole of the forces, now in Auckland ; will follow this day, under

the command of Colonel Despard. They will be accompanied by four guns, under the

command of Lieutenant Wilmot, Royal Artillery, son of Sir Eardley Wilmot, Lieut-Governor

of Van Diemens' Land, who lately arrived from Hobart Town, with Messrs. Boyd and

Kerr, retired officers of the same Corps, as volunteers on service in this Colony.

We think the cold wet season far advanced, for field operations in New

Zealand, and unless very prompt advantage is taken of the fine weather, before

the full moon, great difficulty in proceeding in the bush, and severe privation

to the troops will occur.

The latest accounts from the Bay of Islands

state, that Hone Heke has intimated to the Government that he is anxious for peace

; but not less inclined to carry on the war, if His Excellency the Governor prefers

fighting.- He states that he has been sufficently punished, by the destruction

of his pahs, his canoes, his provisions, and the loss of so many of his followers

- for the little crime, which he has committed, of cuting down the Flag staff

: to which, he was instigated, he declares, by French and American people, who

told him that the English would enslave, ultimately, all the natives.

Heke

likewise urges, that the lives of all the Pakehas, at Koroarika, were at his mercy,

and that he prevented, not only the slaughter of those who left it, but also of

the Missionaries and others, who have remained.

He is anxious, that the Government should let him and Nene fight out their own quarrels and not interfere. However rebellious and unlawful the conduct of Heke, it is very far different to that of Kowaiti and Pomare. Heke displays a nobleness of character, with feelings that, under other circumstances, would be deemed patriotic ; and he has, certainly, proved himself not only anguinary as many applauded heroes of civilized nations."

The new Governor, George Grey, brought troops with him, to provide a total 1,000 men, to lay hold of this native with "a nobleness of character" nonetheless, and with Waka Nene's 400 to 500 he commanded a small standing army - Hulme pursued Hone Heke, and eventually over-ran him, and his warriors, at Ruapekapeka Pa.

In the image above, the British are encamped in a 'friendly' pa - the foe are on the hill opposite and cannon fire is being directed into it. The Union Jack flies in this distant corner of the Empire. The pa was over-run, burnt down, and Hone Heke was taken prisoner.

Hone

Heke's belief, that the English should go back to England was hopeful, but naive:

"Because

God made this country for us it cannot be sliced - if it were a whale it might

be sliced - but as for this - do you return to your own country, to England which

was made by God for you."

He was later pardoned by Governor Grey, married Hongi Hika's daughter, Hariata in 1837.

This renowned figure in New Zealand's history died in 1850 of tuberculosis (neither his daughter nor son from his first marriage survived infancy).

In Wellington in 1844, Wakefield had aquired land for the New Zealand Company to on-sell to settlers, some 160,000 acres, and an understanding was reached whereby Maori kept their reserves, pa, cultivated and burial grounds (16,000 acres) - the boundaries of the original sale were redrawn to include 209,000 acres (most of Wellington) without telling the Maori. Land was never relinquished, nor paid for.

A year later Commissioner William Spain found the sale to have been invalid, but the Government and the New Zealand Company ignored his findings. Wakefield offered £1,500 as "compensation".

However, "Ngati Rangatahi were forced out of Heretaunga, and their property in the valley was pillaged and burned .. followed by armed conflict .. with the war subsequently moving north to Porirua".

In 1846 Andrew Gillespie and his son were killed by Maori, but it appeared to be an isolated attack - fortifications around Wellington were sturdy and people hoped that the unease would settle down. But it was not to be.

Boulcott's Farm, just out of Wellington, erupted in gunfire one dawn in 1846, and 7 soldiers from the 58th regiment were killed. The bugler was axed to death as he was attempting a bugle an alarm - and this instrument was carried away into the forest to be blown, taunting the pakeha.

Governor Grey landed troops, 800 soldiers and 200 sailors, from "HMS Calliope" and moving inland to Plimmerton siezed Te Rauparaha - who had not been involved! Te Rauparaha was held in prison without charges or trial.

Grey hoped to decapitate the tribes by kidnapping the "Naploean" at their head. Certainly, he robbed Te Rauparaha of his 'mana', or prestige, and Grey's increased.

Te Rangihaeata, who had instigated the raid, fled, and retired to Paeroa, and left the British in peace.

His colleagues, however, who had arrived from Wanganui to help him, returned home and created disturbances of their own.

In 1847, warriors of the Ngati Haua iwi, instigated by the chief Te Mamaku, attacked the farm of James Gilfillan at Matarawa, killing his wife and three children.

Gilfillan and a daughter escaped.

Captain J Laye, who had built the Rutland Stockade in Wanganui, captured the renegades, with the help of friendly iwi - an attack was expected to attempt to free the rebels, so Laye tried, convicted, and hanged four of them immediately.

Maori were becoming very resistant to selling land, now fully understanding that the pakeha concept of a purchase was the irretrievable loss of the land, and by 1858 the Maori King Movement had been born. Not only was it a movement to prevent the loss of land, but also a political and police movement - Maori wanted rule of law too like the pakeha.

In his favour, Grey had overseen land purchases and had been determined they should be fair and appropriate: he also gave money to mission schools that Maori should learn to read and write; he built hospitals for Maori; he lent money to tribes. By purchasing ploughs and farming tools, and even flour mills, some tribes became wealthy. Some became rich, owning coastal ships, and trading.

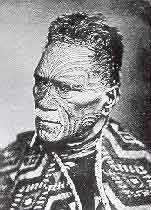

The first Maori King, Potatau Te Wherowhero had been succeeded by his son (above) Tawhiao, and by 1863 most NZ Maori adhered to the movement.

The movement was intended to preserve sovereignity, where New Zealand Maori would govern themselves - and if that included not selling land, then so be it.

The trouble was, Pakeha believed that New Zealand, as a whole, was theirs.

In 1860, Governor Gore Browne, who had replaced Grey in 1855, had a reason to teach a "sharp lesson" to Maori that land was going to be obtained from them - and this is when the first bullets of the Land Wars began to fly. In 1859 the Pekapeka block of land (where 200 Maori were living) at Waitara in the Taranaki had been "sold" for £600 by a chief of the Atiawa, Te Teira, perhaps mischievously - as revenge after a woman he had kidnapped found refuge with Wiremu Kingi.

The

senior chief, Wiremu Kingi te Rangitake (above),

a staunch

King movement adherent, had annulled the sale of the land, and surveyor's markers

pegs were pulled from the ground. Governor Browne was determined, and war erupted

- soldiers were sent to the Taranaki to fight huge numbers of Maori, who came

from all over the North Island - the steam corvette 'Victoria', which was

the State of Victoria's (Australia) Navy, brought Australians on their first official

(under the Articles of War) overseas campaign.

New South Wales sent gunboats.

The British had a problem however. They might have been an elite corps of soldiers, seasoned in Europe but the wily natives were formidable adversaries, and around New Plymouth, like a fortified wall, the Maori had erected a series of pas, or forts - New Plymouth was encircled, was essentially under siege.

Ruapekapeka Pa, 1846

barricade/trench/two

barricades/ artillery shelter/

barricade/shelter/barricade/barricade/trench/barricades

The Maori pa, or fortified stockade, gave protection that proved very difficult to overcome. The Commander, Pratt, knew the techniques of "sapping", or digging under forts, and immediately put it into practice - however as British sappers, dug toward a pa, the Maori would abandon it, and throw up another one - allied with guerilla-style attacks in the bush, they proved elusive, and the British lost as many skirmishes as they won.

In

fact, the attack on Puketaukauere Pa, mid 1860, was such a military disaster,

that one modern commentator, James Belich, has called it,

"one of

the most clear cut and disastrous defeats suffered by Imperial troops in New Zealand"

There were two pas at this site, one that appeared lightly defended, and the other more heavily fortified. The smaller one was actually an ambush - when the British attacked it, they were in turn attacked and caught in swampy ground and axed.

In 1861 of this Taranaki war, a ceasefire was called, even though the British had not achieved "one decisive battle", and the Government agreed to an enquiry into the land sale - it did not eventuate.

Browne saw that his problem lay in the King Movement itself, and reasoned that if he were to invade it's heartland - the Waikato - he could destroy it. He also believed that the Waikato tribes planned to invade Auckland.

However, Governor Grey, who had returned to NZ from governing Cape Province in South Africa, to replace him, looked at Browne's invasion plans, and modified them - he put General Duncan Cameron, a Crimean veteran, in charge.

Skirmishes erupted, at the same time, in Taranaki, where farmers were driven from the land at Tataraimaka. Maori attacked a column of soldiers at Oakura in 1862 but one escaped to raise the alarm in New Plymouth.

Cameron attacked the warriors, who had retreated to their pa, with artillery, and the guns aboard the schooner "HMS Eclipse" ( which, 2 years later, would be siezed briefly by Maori in Opotiki), followed by a bayonet charge that overran the Maori, surpressing them for a time.

Taranaki was to feature later in the birth of a movement known as Pau Marire, or "good and gentle", later simply the Hauhau movement - in honour of the angel Gabriel.

Northern Maori then began raids on the outskirts of Auckland.

In 1863, Cameron led 14,000 men down the Waikato River.

This was a huge army in the NZ bush, equipped with two river gunboats - the 140 ft "Pioneer", built especially in Sydney for the Waikato River, and drawing only 3 ft, and the "Avon" - with telegraph, and with modern armanents to bring to bear against 2,000 warriors armed at best with muskets that were probably manufactured in Birmingham - they were cheap, rough guns thrown together for a "mass market" and misfirings and backfiring was common.

The other problem Maori had was a shortage of ready-made ammunition, and often they had to make their own.

In August of that year, the gunboat "Avon" fired on the Meremere Pa, enroute Ngaruawahia, the home of the Maori King; "Pioneer" then followed, in September, shelling the Pa, and it was abandoned. Cameron made Meremere his base to prepare for the next leg, but it had taken 3 months for him to claim it..

Image below, Alexandra Redoubt. The British flag is flying 302 feet above the river - the canoes are manned by soldiers of the 65th Regiment, keeping Maori off the water.

Volunteers

were also being marshalled at this time, by the British, for a militia to be called

the Forest Rangers, and this comment by a would-be volunteer militiaman may typify

the attitude of the time,

"I may therefore tell you that it is not

for the pay, neither am I anxious to get a name, but if I get through, I shall

expect a lump of good land"

to

which Grey is reputed to have replied,

"I will give you not merely

a lump, but a large slice in the choicest part of the Waikato"

One man to join the Forest Rangers was a painter, and journalist, and who had written a book about his voyages through New Zealand, an ex-patriate of Poland, Ferdinand Von Tempsky.

On patrol Von Tempsky's excellent skills led to him being made a British national, and later given the rank of Captain.

Von Tempsky was one of New Zealand's large and charismatic figures.

"(1828-68) Prussian-born adventurer, mercenary soldier, farmer

and gold miner. Son of senior Prussian officer, trained in Berlin Military School

and after serving in the army, went first to Central America, then to California,

living as a soldier and goldminer; to Scotland and then to Victoria in 1856 and

took up farm land. Rejected to lead an expedition into central Australia in favour

of Burke, (Burke & Wills) he joined the goldrush at Coromandel peninsula,

NZ, in 1859. Joined the Colonial

Defence Force in 1863 rising to the rank of captain. He was a major factor in

overcoming stout Maori resistance at the battle of Orakau near Te Awamutu in 1864

against Rewi Maniapoto's defenders. He was arrested in 1865 for refusing to serve

under his junior in precedence major Fraser. He

died holding an exposed position against Titokawaru's warriors. His body was

burned on a funeral pyre by the Maoris. He was widely admired for his courage

and energy, but deprecated by many for his Prussian arrogance."

The Maori responded as they had at Taranaki, using guerilla warfare, expendable pa, and even getting their hands on some artillery.

Cameron's army had been held at Meremere for an incredible 3 months, and when the Maori ran out of ammunition for their fieldpieces, they had improvised with anything that would go down a cannon barrel.

Finally Cameron broke through to the second line, at Rangiriri, and was repulsed 8 times - despite greater numbers, gunboats, and cannons.

Assaults on the pa were simply thrown off, with great loss of life. Ultimately this battle was regarded as one of the severest in the Maori Wars.

When the Pa finally fell, because the defenders slipped away into the night, the remaining 183 prisoners who had run out of ammunition, were taken to Kawau Island, in the Hauraki Gulf - from where they escaped to take refuge with the Ngapuhi.

Cameron then fought on to Ngaruawahia, then Cambridge, and on to the final defensive line at Orakau under the command of Rewi Maniapoto, near Te Awamutu.