Maori adapted to their new world almost instantly.

The arts of architecture, carving, sculpting, tatooing, weaving, song, poetry, and oratory; the definitions of warlike behaviour and strategems; the civil engineering skills; the arts of seamanship and navigation; and even the respect for, and encouragement of children's games were all great achievements.

| The Maori devised tools and implements from the scant materials available - bone, shell, greenstone, stone and wood - to wrest a living from the land. |  |

In that process they created a unique and functional society.

The primary injunction of the Maori is that the whanau continues - whanau is a hard word to translate, but roughly it is not husband, wife, children as we understand the nuclear family.

The whanau are the grandparents, the parents and the children, and all brothers and sisters - aunts, uncles, cousins, nephews, nieces etc - in short the common threads in the weaving of a life that a man or woman enjoys.

The whanau shared a house and lands and fortunes, and this unit was the building block of society. Groups of whanau created a larger hapu, or sub-tribe, and sub-tribes themselves created an iwi.

Property was not exclusive. A person who "owned" something owned the use of that thing, for that time, but did not own it forever, as Pakeha would understand ownership.

A warrior might own his weapons, and it was understood that they were for his very own use. A woman might own a treasure box to keep her personal and precious items.

The most treasured possessions of the Maori were the implements, tools, weapons or jewellery that had been laboriously made and decorated, and passed reverently down through generations. It might be an adze, a fish-hook, or a carved box.

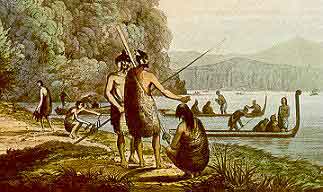

No one person could own a canoe, for example. It was tapu, it was too valuable, and it was owned by the hapu.

The roles of men and women were clearly defined, and people of higher rank had extra privileges - as well as extra constraints and tapu.

|

Another difficult word to anglicize, tapu means sacred or untouchable or secular. Certain parts of the body are more tapu than others, a man's back being tapu but the head even more so. Women did not have the levels of tapu that men had, but as always, there could be exceptions for women of high or noble birth. Building houses or canoes was very tapu, as was the actual planting of kumara or taro, and in the forest or ocean, the life that teemed there was tapu. |

Tapu was the final arbitrator of ordered Maori life - it's many boundaries and constraints regulated what was possible and what was not. Essentially, any irreverence or disrespect would be calamitious.

Nobody would steal from a chief, for his tapu was too strong, and on the other hand, a man with much tapu could become the new owner of something simply by touching it - nobody else would have the stature to touch it after that.

Many difficulties with the Pakeha who arrived in New Zealand arose because of the rigid Maori boundaries of tapu, and the European's totally oblivious transgressions of that tapu - the slaughter of du Fresne in Spirits Bay probably arose from his unintentional but nonetheless serious defilement of tapu.

The newcomers understood the 30-day, 12-month calendar.

They studied and prepared for the migratory habits of birds, some species of which returned to NZ from Russia annually.

| They learnt what berries, ferns and fungi to eat, how to preserve fish, where to find the varieties of shellfood, and how to cook birds in their own fat to preserve them. |

|

The edible shellfish in NZ were bountiful, from freshwater mussels and mud snails to seawater mussels, limpets, paua, pipis, cockles, tuatua and toheroa, as well as scallops and oysters.

The shells were used as small containers for pigments and the paua shell polished and inlaid into carvings and fishhook lures.

For clothing, they harvested a fairly broad-leaved ground plant called flax, thinned the leaves and made fabrics and ropes from the fibres. They augmented their clothing with the skins of dogs, and hundreds, sometimes thousands, of birds feathers, although in some areas tapu cloth, as it would have been prepared in Polynesia, was still being made, although in such small quantities is was only for ear ornaments.

A beautiful cloak made from the skins of kakapo, a noisy, mischievous NZ parrot, and it's feathers, plus kaka skin and feathers, as well as strips of dog skin and hair was discovered in 1881 in central Otago - from the early period, post 1600, it is known as the Hauroko cloak and was similar in style to woven flax cloaks that did not attempt to follow the outlines of the body.

The later style in 1700-1800, known as the classical period, favoured body-tailored cloaks, and ornamentation with feathers and fur was still important.

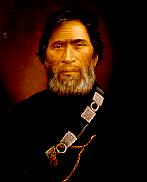

Men needed to be dressed in a short beard at the chin, hair done in a topknot, and a string from waist to penis.

| Facial tattoo was optional, as was a white feather and decorative comb in the hair, a belt around the waist and leg/thigh tattoo. |

In war time however, men would often strip and fight naked, the better for movement and to show their fierce tattoos. Alternatively, a short maro, or kilt could be worn with a belt to carry weapons. At other times war cloaks that had been steeped in water might be worn - the water was intended to dull spear thrusts.

| On formal occasions cloaks were worn, and ornaments like reiputa, tiki or heimatua worn at the neck, and feathers, a piece of tapa cloth, or greenstone ear ornaments ( or shark's tooth ) - and the body may have been smeared with red ochre. |

Women would wear a minimum girdle, plaited cord around the waist, with a bunch of leaves covering the pubic area, with optional tatooing on chin and lips. Hair was usually cut short, and a waist garment was always worn. While the pubic area was covered, the breasts were not necessarily hidden.

Formal costumes were the prerogative of chiefs, and they favoured the dogskin - there were 10 varieties in use through the classical period. Another formal costume was the kaitaka cloak of finely woven flax fibre, and because it was soft it followed the configurations of the body.

| The beautiful korowai cloak (image right) was another finely woven garment decorated with lengths of rolled fibre that had been dyed black, and with black fringe on the borders - it became very popular in the later Transitional period, post 1800 |

After the arrival of the European, and the increase in trading of the beautiful dog skin cloaks, the poor old native dog was extinct by 1830, and the cloaks could no longer be made. The korowai and feather cloaks increased in popularity, but not for long - Pakeha clothes became fashionable, and by 1870 most Maori had adopted Western-style clothing, reserving their own costumes for ceremonial use.

This

Web Directory will always be dynamic ~

all details are flexible and changing