![]()

Art History, NZ, page 2

Of greater eventual value in the development of non-draft renditions were the delineaters of landscapes that resulted from the country's exploration or aspects of its settlement which, though largely conditioned by topographical interests, reflect a sense of identification with the land.

This can be observed in the lyricism of Heaphy's "Mount Egmont from the Southward" (1839) or the watercolours of Bream Head, Whangarei (1850's), in the broader, more earthy landscapes of William Fox (below), the primeval rythm captured by John Buchanan (image page top) in his "Milford Sound, Looking North-West from Freshwater Basin" (1863) - said to be one of the finest paintings ever to come out of New Zealand - or the gentler realism of the Rev John Kinder, the concise townscapes of Edward Ashworth, in the grand panoramic views of Western Otago by John Turnbull Thomson, or the variety of rather mundane views from Charles Barraud.

![Sir William Fox, "On the Grass Plain below Lake Arthur [Rotoiti],Nelson, 1846", Alex. Turnbull Library](images/fox.jpg)

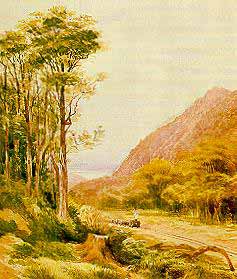

The Italianate versions of the bush near Auckland by Albin Martin (image below) should not be dismissed, nor the amateur artists like James E FitzGerald and Frederick Weld, Emily Harper and Captain EE Temple who pictorially recorded the opening-up of the land for grazing and agriculture.

In his small, neat, full-length portraits of Maoris, Jospeh Jenner Merrett continued that documentary line of painting with it's quasi-scientific justification that was, in a different way, taken up by some of the soldier-artists during the Land Wars.

Lt Horatio Gordon Robley (below) sympathetically portrayed the Maori, either in battle or in everyday living, and made a study of the moko.

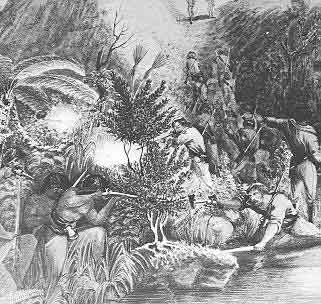

Gustavus Ferdinand von Tempsky (below) revealed a more romantic view in picturing the skirmishes between Maori and his Forest Rangers.

The best account of ordinary military life is in the accomplished watercolour drawings of Lt/Col Edward Arthur Williams while Henry James Warre showed a greater fascination with the Taranaki bush, and Mt Egmont, than with ordinary military matters.

Towards the end of the 1860's and into the 1870's the conventions of romantic realism began to acquire informality as the physical expansiveness of the land was gently dramatised by the luminosity of atmospheric light in which nature acquired a rough-hewn contemplative aspect.

This was most apparent in the paintings of John Gully (image below) ...

...and William Matthew Hodgkins who, working in the less troubled south, used the natural grandeur of the Southern Alps.

This trend was encouraged by the extended visit of Nicholas Chevalier who, in 1866, received financial assistance from the Canterbury Provincial Government to undertake a "pictorial survey" of Canterbury and the Southern Alps.

In a quieter way the same trends are observed in the work of Kinder, James Crowe Richmond, in the precise Otago Peninsula landscapes of Laurence William Wilson.

Although landscape painting remained under the dominance of topography, this basic element became heightened and refined by Alfred Sharpe, given popular elegance by John Barr Clark Hoyte (image below)...

... a confined informality by Thomas Cane, or carried in several directions from the factual to the picturesque under the plodding skills of Charles Blomfield and artists of similar talents.

The growing propserity, boosted by the gold rushes in the Coromandel, Otago and on the West Coast, was accompanied by growing aspirations among artists and their supporters.

This

Web Directory will always be dynamic ~

all details are flexible and changing