The Frenchman M. d'Urville was back in the country again by 1840, charting the coast with 2 ships, "Astrolabe" and "Zelee", while the French whaler "Cachalot", captained by Jean Langlois, had arrived earlier, in 1838 - Monsieur Langlois had purchased land at Akaroa for F6,000.

He had returned to France, and formed the Nanto-Bordelaise Company, to assist French settlers out to New Zealand.

The French Government provided a warship "L'Aube" commanded by Captain L'Aube, and a vessel for the Company, the "Comte de Paris".

While the French were at sea however, sailing towards what they believed was a small piece of France in the South Pacific, the NZ Governor, William Hobson, learnt of their imminent arrival - and urgently despatched Capt Stanley, on "HMS Britomart" to Akaroa, with an English flag.

When the emigrees landed, they were startled to find the Union Jack flying from a tall flag pole at Green Point.

Sixtythree French settlers had arrived, and while the Nanto-Bordelaise Company later disappeared, these pioneers established a genuinely French-flavoured part of New Zealand.

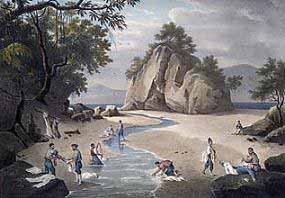

By 1840 New Zealand had around 2000 Europeans, (50 Americans, 20 French, the rest British) and it is estimated that 1000 of them were at Russell - then named Kororareka - which had a church, five hotels, scores of grog shops, theatre, billiard-halls, skittle alleys, finishes and hells (gambling houses) - in 1838, 56 American vessels, 23 English vessels, 21 French vessels, 24 from NSW, 1 German and six coastal vessels arrived at this busy Bay (image below)

In the North Island, in that year, probably the single most important document in New Zealand history, the Treaty of Waitangi had been presented by William Hobson to chiefs around the country - and was being signed at what is now known as Treaty House, at Waitangi, by over 500 of the rangatira of the tribes of Aoteoaroa, and Hobson, representing Queen Victoria. Interestingly, 540 chiefs did not sign the Treaty, being suspicious of the Pakeha.

The Treaty (English and Maori versions here) was originally drafted in English, and then translated into Maori by the missionaries Henry and Edward Williams.

This document, that has become a touchstone of the realtionship between Maori and Pakeha with repercussions through the century and a half since inception, was drafted in only 4 days - and not by lawyers but by 3 amateurs.

It has been argued that the Treaty was drawn up - not to assist Maori or to establish a bona fide relationship between the indigenous population and the newcomers - but to perform the function of a diplomatic protocol that would precede the annexation of a country. In other words to "legitimise" the annexation in the eyes of the world.

It's purpose was to legitimise annexation, but it's driving force, it's need for urgency, was to facilitate land sales in which the Crown would be the agent.

The translations were imperfect.

Perhaps most significantly of all, in the term, granting Maori "te tiro rangatiratanga", authority over their lands, dwelling places and treasures.

The printer Colenso, doubting that the Maori present at Waitangi understood the terms, voiced his concern at the time, but was brushed aside by Hobson.

Hobson needed sovereignity quickly, and in May he declared NZ a colony - despite still collecting signatures.

It was not all plain sailing, even within the ranks of the Pakeha. In Wellington, independantly-minded settlers were flying the NZ Independance flag, assuming authority from the local Maori, and Hobson needed to supress such dangerous ideas, which he did, despatching Willoughby Shortland with 30 solders to demand Crown allegiance.

Constable Cole was sent ashore when they arrived, to pull down all NZ flags.

Hobson died in 1842 and was replaced by Governor Robert FitzRoy, also a naval officer.

The Treaty, where New Zealand was annexed by England, may have been primarily to consolidate and control land purchases from the Maori into the hands of the Crown - it had enormous repercussions however for Maori, and over a hundred years later, is regarded by some New Zealanders as an honourable founding document, by others as simply erronous, and by others as exploitation.

Certainly, the Treaty raised complex questions - coming immediately after the musket wars, where huge segments of Maori tribes had been killed and others totally displaced and subsumed into conquering tribes, did it mean that the land held at the moment, suddenly acquired by iwi with muskets, would ignore previous land use and occupation through the past centuries, and essentially legalise the seizures?

Further, did the Maori chiefs signing the Treaty really understand the wording, and the concepts, embodied in it, that they would become subservient to a distant Queen, rather than rule as equals?

A moot point is of course the status of the Treaty in the 21st Century - when the document may never ever have been intended to be such a weighty and defining agreement.

The Waitangi Tribunal would be formed 135 years later to examine these and other disputes, and attempt to right injustices.

However, the Treaty flung opened the door on emigration into New Zealand in a century where many Europeans were on the move - escaping famine, and the social class system that doomed the majority of stay-at-homes to a life of struggle and inequity. North America, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand were new lands of hope for millions.

By 1841, the New Zealand Company had established itself firmly both in Wellington, and across Cook Strait, in Nelson - and were actively encouraging emigration from England.

The Crown, meanwhile, was also rapidly aquiring land.

In 1844, 34.5 million acres were bought in the South Island - it was just about all of the South Island.

By 1846, the Crown did have it all.

New Zealand.org.nz Homepage here