The 30-year period of sustained European emigration to New Zealand had begun. To leave Europe was not a light undertaking - the journey to New Zealand took between 3 to 5 months on overcrowded, unsanitary, bleak and often life-threatening ships. No water for example, was available for laundry, and the advice for bathing was to go on deck in the day, wearing bathing togs, and allow the sailors to fling seawater on you, as they washed the decks.

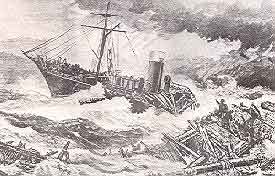

Many

ships disappeared, on the long slog down to the Cape of Good Hope and then around

the world to the country that was to have been a new start, never to be heard

of again. Ships wrecked along the Ivory Coast, sank in the icy southern waters,

and even if they managed to reach New Zealand, risked foundering and gales even

as the new country was within sight.

("Forrest Hall"

aground at North Cape, image above and "Tararu" below)

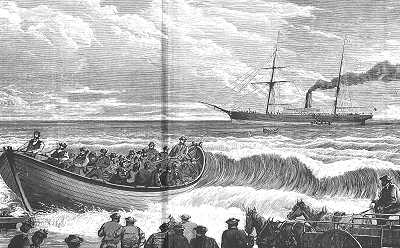

Landing in the new country was also perilous. The ship would anchor off-shore, and long surf boats would ferry passengers, belongings, livestock, and supplies to the shore.

Leaving

the home country, colonists were advised to treat this new vocation as seriously

as if they were embarking on a career like medicine, or as if they were about

to tackle the climbing of a mountain,

"If indeed systematic colonization

from this country should ever be promoted on a large scale, it will be found most

important to establish schools and colleges in which such an education shall be

given"

Colonists were generally young - in 1850, the "Charlotte Jane" berthed at Lyttleton, with 151 passengers: 49 were children, and 11 were over 40 years of age - the remaining 91 were under 30 years of age.

Youth was an assett in the new country, because pioneer life was hard.

Death was not unusual, caused for children by drowning, fire or simply neglect. For adults, overwork, childbearing or septicaemia claiming women, and cave-ins, drowning, crushing, gunshot, blood poisoning, and epidemics carried away the menfolk.

They were isolated, tens of thousands of miles from their heritage, and in a strange and primitive country where walking was the normal transportation.

Single men had no women to marry, other than exploring realtionships with Maori, which created "society" problems peculiar to the era.

"When he does emigrate, the average Anglo Saxon generally settles down and becomes what the world calls a useful, patriotic citizen, and when he dies his most flattering requiem would be he left a lot of money. The impulse drove me out into the world, but the desire to settle down must have been omitted. As here I am, after 40 years, mostly crouched under a piece of calico or a sheet of bark a homeless almost friendless vagabond, with a past which has little to show - the general public at least - of work done, and a dreary future ..." wrote Charles Douglas, neither regretting nor extolling his wandering life in New Zealand.

Colonists were drawn to New Zealand for the usual reasons that people leave any country, and in this new one, there was the prospect of becoming a landowner, of setting up in business, of achieving a status unavailable in the old country - and if land was unavailable or unaffordable, of making a living panning for gold ...

... or scratching at the gum fields for amber.

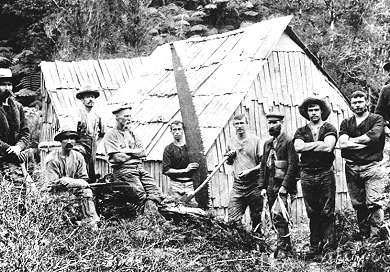

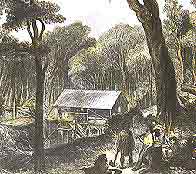

New Zealand's native tree, the kauri, was especially sought after, as a long, straight, hard timber that was nonetheless easy to work.

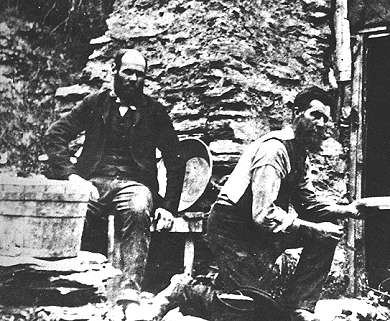

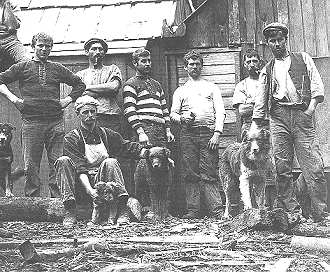

Images below, Northland timber camp, another kauri timber camp, and a mill in the bush:

The later development of the culture of New Zealand, with it's self-reliance, fortitude, imagination, and a willingness to "give it a go" is a result of the achievements over adversity that the early pioneers had to quickly find.

As the colonial pioneers built their own small version of England at the bottom of the world, we must never overlook a thread that ran through the development of this culture that was utterly indigineous - that of the parallel growth of the Maori, who were influenced by, and in turn influenced, their Pakeha neighbours.

Essentially,

Maori had an enormous sense of who they were, and their status in the country.

Maori took from the Pakeha what was valuable and rejected the rest, often forming

temporary alliances to do so, and at the same time earnt the respect of the Pakeha.

Contemporary accounts highlight the speed with which Maori could incorporate the possessions and the ideas of the Europeans, and give them a unique Maori-ness, which, filtering back into the society and the outlook of the new colonial New Zealanders, would in later years give them icons which would set them apart from those at "home".

In the next century this unique forging of cultures created a new human being - a "New Zealander"

Kiri Te Kanawha, proudly owned by both Pakeha

and Maori

New Zealanders, Pakeha and Maori, were developing together, and it was the adaptability and the enthusiasm of Maori that allowed it to be. Elsewhere in the world, indigineous people invaded by colonial powers had been cowed and destroyed. The Maori were to emerge stronger.

In fact, the first such test - a rude awakening - was to appear soon, when the Maori realised that the Pakeha desired large areas of land and self-governance, and believed that they were entitled to it.

By 1860, constant arrivals had increased the numbers of Pakeha to around 40,000 in the North Island, with 60,000 Maori, and there was a corresponding extension of Pakeha control over geographical areas.

Where Maori owned large tracts, neighbouring Pakeha were largely governed by Maori beside them. Practical politics was more persuasive than a document in Auckland, and Maori enjoyed the mana (and trade) that their Pakehas brought into the region.

Land was not valued as such, but the control and power over it was.

Perhaps more germanely, the act of selling land brought the purchaser into the tribe, increasing the tribe's stature. The purchaser became an object whose own prestige became part of the tribe - the purcahser became purchased !

"The purchaser became one of the most valuable possessions of the tribe; the chief called him "my Pakeha" and the tribe called him "our Pakeha". he traded with them, procured them guns .. promoted their importance, and was at the same time dependant on them for protection and completely at their mercy...all his greatness and grandeur were their possessions and rebounded to their credit. But as the number of Europeans increased these relations were altered; a sale involved parting with the dominion of the soil" observed John Gorst, in 1864.

When Maori sold land, they believed that they continued to exercise control over it, by virtue of their strength, and of course they believed the also retained power over any Pakeha living on that land.

A land sale, for Maori, did not draw a line in the soil that said "mine" and "yours" but rather "mine" and "yours to use".

Maori still believed that they were chiefs in their own land, as guaranteed in the Declaration of Independance and the Treaty of Waitangi.

Wakefield, of the New Zealand Company, who were keenly purchasing land, is reputed to have said, that Maori "betrayed a notion that the sale would not affect their interests (or) prevent them retaining possession of any parts they chose or even of reselling them"

So on one hand, Maori selling weren't really "selling" as Europeans understood the word, and on the other hand, Europeans were determined to have the land regardless.

As the numbers of Pakeha increased, and their collective power increased, Maori would lose control of their land, and this was becoming alarmingly apparent to some.