The first settlers at Rekohu, known to us as the Moriori, followed 500 years after the Great Fleet of Maori that had arrived in New Zealand. They had no word for themselves.

As fas as they knew, they were all that there were of humankind, and the closest term was "tchakat henu" or "people of the land".

Where did they come from ? One mythology, which differed among the tribes, had as their genesis that "the people" had come from Te Aomarama and Rongomaiwhenua - Sky Father and Earth Mother.

Their oral tradition said they had come from Aotea, but this was not necessarily Aoteoroa - "aotea" means distant, far away. It is probable they originated in Polynesia of course, but another myth tells us that the Moriori originated on Pitt Island, which is nearby.

Henry Skinner, ethnologist, observed in

1919 that,

"the Moriori culture and the southern culture of the Maoris have points

of relationships far and wide in the Pacific .. closest with eastern Polynesia

and particularly with Easter Island" (image below)

| The Moriori present as strikingly different people to the New Zealand Maori, so there may be some difficulty in "lumping" them in with the Great Fleets of the Maori, which is the most currently-held belief, detailed by Sir Peter Buck (with suggested canoes below) |

The first ancestor, according to this belief was a human rather than a god-creation, Kahu of the Tane canoe - he later returned to NZ, leaving offspring and wife behind.

|

Canoe

|

Chief

|

Arrived

|

Tribes

|

|

| Tane, from NZ | Kahu | Kaingaroa or Tuku, Rekohu | Aotea | |

| Rangi Mata | Mihiti | N.Coast of Rekohu | Wheteina | |

| Rangi Houa | Te Rakiroa | N.coast of Rekohu | Wheteina | |

| Oropuke | Moe | Rauru |

As we see, two canoes later arrived, with Te Rakiroa, and Mihiti, fleeing the Rauru tribe, and several generations later a third canoe arrived with Moe of the Rauru themselves.

Fighting inevitably broke out between Rauru and Wheteina, but chief Nukunuku stopped it with a remarkable proclamation (below)

The Moriori were immediately disadvantaged in their new land.

It was an unforgiving and harsh island, especially after the hazy climes of Polynesia - Rekoha was named after the mist that clings about the Island, "misty sun". The satellite image (below) shows the streaming clouds.

While New Zealand was a lush and productive farming country for the new Maori settlers, and they simply continued with the farming culture they had left behind in the Pacific Islands, only with even more berries, birds and fish thrown in - the Moriori's island of Rekohu could not sustain the same culture.

The Moriori soon became a skilled hunter/gatherer society, subsisting primarily on fern root, karaka berries, eels, birds like the penguin, taiko and the large albatross, netted fish, large shellfood and seals.

Most food resources were at hand - the longest treks required were to seasonally cull albatross (image below), which meant travelling to the Pyramid, 56km to the SE of the central meeting place at Waihora, or 69km to the Forty-fours in the east, or 53km to the Sisters in the NW. The preflight birds were particularly valued.

They established a careful working relationship with the environment, taking enough for food and clothing, and never any more. They were conservationists, essential for survival.

For example, they maintained their seal populations largely intact, by limiting the extent to which rookeries could be exploited. At the time of the first sealers, Moriori still had a rookery within 400m of occupations, and a seal population estimated at 20,000, by killing only older male seals, and removing all carcasses which would otherwise deter further breeding.

It worked - Moriori lived half a millenia on these isolated islands, until European sailing ships appeared.

The Island population, 7 tribal groups, stabilised into around 40 small villages, each with up to 50 people, and the central Waihora.

In any hunter/gatherer society, life can be very tenuous, and inter-tribal war can threaten extinction. In fact, such wars are a luxury that can be tolerated by settled/farming societies only because new members can be raised and fed with some degree of assurance that the tribe as a whole will survive.

The Moriori, lacking that assurance, had abandoned warfare.

The chief Nukunuku Whenua established

a precept, that disputes would be settled by duel using a stick called tupurari,

which was a thumb's thickness and an arm's length - the winner would be the

first to draw blood, and the fight would then stop -

"only fight til you draw blood, then stop".

Nunuku had also laid a curse, that should anyone defy the law, "may their bowels rot".

Because the native trees were not suitable for oceangoing canoes, and the original canoes had rotted away, the Moriori were isolated.

This was excaberated by the Little Ice Age around AD1400 when, even if it were possible, ocean-going expeditions would have been more hazardous than ever. The tribes became self-sufficient and contained on their small Island.

In 1791 a European Royal Navy ship, the brig "Chatham", arrived and Lt Broughton immediately claimed the Island for King George III, ignoring the inhabitant's claim to many centuries of prior occupation.

The Moriori and Europeans - representatives each of completely alien races - met each other at Skirmish Bay, and the Europeans, strolling the beach, came between the inhabitants and their canoes, and nets.

That was a dangerous situation for the Moriori. Fishing was survival - to lose boats or nets could mean death.

The locals rushed the sailors in a display of aggression and shots broke out. A musket ball went through the arm and chest of one native, Tamakaroro, and he died.

The Moriori fled and discussed what had happened with these strange beings, and resolved that they had done a bad thing. The Chief's newphew was now dead.

The next day, the natives deliberately laid all their fishing spears on the beach, and the Chief approached the European commander with a length of seaweed, a clear peace symbol. This was accepted.

|

"The Men were of a middling

size .. their Hair, both of the Head and Beard, was black and by some

worn long. The young Men had it tied up in a knot on the crown of their

Heads; intermixed with black and white feathers....their skin was destitute

of any marks, and they had the appearance of being clean ..their dress

was either a seal or bear skin, tied with sinnet, inside outwards, round

their necks, which fell below their hips; or mats, neatly made, which

covered their backs and shoulders.." remarked Broughton |

Inevitably, more ships arrived in the Chathams now that it had been re-discovered, including American whalers, and word soon spread of of this small island that was replete with seals.

By the 1830's all the seals were gone, plundered for their fur.

Without seals, the Moriori had lost a food source, and more importantly, their winter clothing - while Europeans were guaranteed at least another season of fashionable attire.

At the same time, much of the Island bird life was decimated by the sealer's guns.

The Moriori also fell foul of diseases like influenza and VD, of alcohol degradation, and of European guns and European disdain and abuse - but through it all they stayed loyal to the tradition of non-violence.

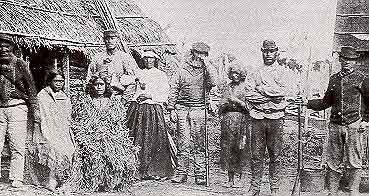

Europeans

also lived on the Island by then, and the Captain of the brig "Bee"

reported that there were

"eight to ten runaways on Chatham Islands" - as well as people

from other parts of the world (image below) and around

1600 Maori.

In general, both Maori and European regarded the unassuming, peaceful Moriori - who undoubtably were in culture shock, common to races "discovered" and overwhelmed by Europeans through these centuries - as a degenerate and lesser race.

From Left, Nationalities: Moriori, Maori, Maori, Hawaiian, Moriori, American,

Maori, Hawaiian, Azores

The Moriori, disregarded in their own

land, and with their traditional food and clothing resources obliterated,

faced a bleak future, despite being described in 1835 as

"cheerful, full of mirth and laughter"

Their future however was about to get very very much worse.

This

Web Directory will always be dynamic ~

all details are flexible and changing

This

Web Directory will always be dynamic ~

all details are flexible and changing